Crude Oil: Slippery Stuff

Way back in the mists of time, or 1952 to be exact, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company had just been kicked out of its main supply area – Iran – and was busy changing its notepaper to read British Petroleum (BP). Preoccupied as they must have been with this, the men in charge suddenly realised that they really did not have much of a clue as to where most of the world’s oil might be found, or indeed how much was actually being produced. So, they told two of their own to go and find out. So ‘Jamie’ Jamieson and ‘Dusty’ Miller started what would subsequently become the BP Statistical Review of World Energy.

It was not as easy a task as it might sound. Google was not around and the US companies in particular, remembering the destruction of Standard Oil in 1911 on anti-trust grounds, were pretty reluctant to collaborate. Nonetheless Jamieson and Miller did eventually come up with six pages, which was “restricted” in deference to “anti-trust” and stated that world production of crude oil was 12.2 million barrels a day (mbd) and that 52% of the reserves were in the Middle East, 27% in the US, 8% in Russia, 6% in the Caribbean and the rest somewhere else.

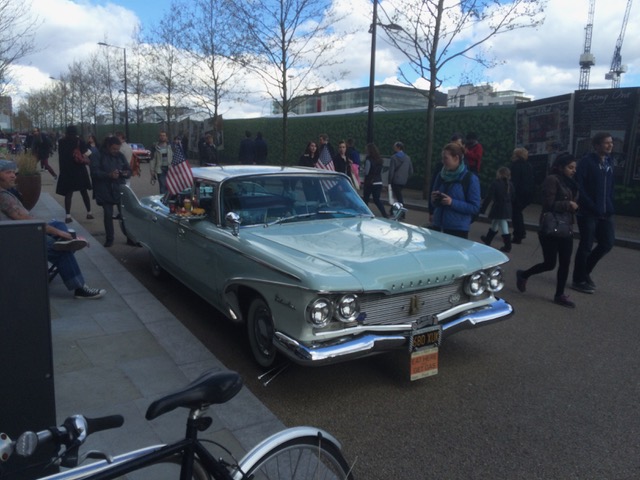

This, at least, puts some perspective on the current figure for crude oil production and consumption, which in 2021 was around 89.9mbd, having fallen back due to covid from 94.6mbd in 2019. In short, we now consume seven times more than the amount of crude oil we did 70 years ago. This is perhaps a surprise in the context of an average US fuel consumption per car in the 1950s of 14.5 miles per gallon. Or perhaps not, as there are now, after all, around 1.4 billion cars on our global roads, running at an average of 25.4 mpg.

One can, of course, have two widely different attitudes to this astonishing growth in oil consumption. The first is that the oil industry’s endeavours have gigantically added to global prosperity, mobility, heating and light, through an astonishing technical ability to find and produce oil, even in very deep water. Or one can suggest that it has, in later times at least, knowingly gone out of its way to destroy the planet. Certainly, one can say with a certain amount of proof that virtually everybody on the earth has benefitted in some, perhaps minor, way from its role in providing locomotion, even if its global consequences and its continued growth are no longer acceptable.

If anyone fails to see its importance, then look no further than the impact of the price of oil on the global economy, although when inflation is taken into account, this may not have been quite so astonishing as the history books suggest. Back in 1952, the price was $2.77 a barrel for West Texas Intermediate, the US price marker. (Brent crude, the current global price marker, was still undisturbed deep beneath the North Sea.) Put into 2022 dollars this was around $30 a barrel. It is now $74.11 a barrel, but taking inflation into account, this is considerably lower than it was in 1980 and 2008, when it would have been $134 and $125 a barrel respectively in 2022 dollars.

In a curious way, when people think about crisis in oil supplies, the name that always comes up is OPEC, or the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries. Reference is then made to 1973 and the OPEC embargo, which related to the West’s support of Israel and the 1979 crisis that occurred as a result of the Iranian Revolution and the Iran-Iraq War. In practice the near tripling of the price in 1973 owed more to scarcity than politics and because it was sustained, triggered off a global production drive, which included the North Sea. Prices at $12.21 made the offshore viable, when $3.39 a barrel did not.

Equally, the 1979 crisis, which saw nominal prices rise from $14.95 a barrel in 1978 to $37.42 a barrel in 1981, also saw them collapse to just under half what they were in terms of constant dollars six years later. In fact, by 1986, the price was actually lower in constant dollars than it had been in 1973 before all the fuss. What did change as a result of the emergence of OPEC was the end of the dominance of the “Seven Sisters” oil companies and their subsequent cannibalism when they ate each other. With this came an openness about prices and quantities that would have been way beyond the dreams of Jamie Jamieson.

This openness and a new era came about partly through two remarkable individuals: Wanda Jablonski and Jan Nasmyth. Between the two of them, they invented the “price reporter” or one of the most tedious jobs in modern journalism.* Jablonski could, with pardonable exaggeration, be called a ‘Godmother’ of OPEC, although that was probably not her intention. As early as 1959, as a journalist with a US trade paper, she banged Saudi and Venezuelan heads together in Cairo about controlling their own destinies. Meanwhile, she bluntly told western oil companies that their days of control were coming to an end. In 1961, she founded Petroleum Intelligence Weekly (PIW) which became required reading, in spite of the fact that “Wanda” was not the easiest person to work for.

Nasmyth was another matter altogether and one of nature’s gentlemen. A former distinguished British soldier, father of the Garrick Club and leader in the creation of Heathrow Airport, he founded Petroleum Argus in 1970 in recognition of the need for far more pricing and quantity data right across the industry. Unlike PIW, Argus has not merely survived but has become the primary source of information on petroleum, gas, coal, electricity, biofuels, LPG, metals, chemicals and fertilisers with 30 offices around the globe. Under the formidable guiding hand of British businessman, Adrian Binks, it grew spectacularly, currently employing 1300 people. After Nasmyth’s death, it was partly sold to the equity firm General Atlantic for a cool $1.4 billion in 2016 and is still going strong.

At least part of the reason for mentioning the data suppliers here, apart from the contrast with BP’s level of knowledge in 1952, is that this data is the foundation point for a huge financial speculation business that, in practice, apart from the data, has nothing whatever to do with the oil industry itself. The next major oil crisis came in 2007, with a familiar mix of reasons. China’s demand had gone from 3.4 mbd in 1995 to over 7 mbd in 2005, while India’s demand also increased. Much of the Far East was subsidising fuel prices, the dollar was falling and production was declining in the US, the North Sea and Mexico. Nigeria suffered from severe unrest in the Niger Delta.

In addition, a huge new tail had added itself to the oil business dog in terms of the futures market. There is nothing wrong with making sure of adequate supply, by buying a futures contract to enable a company to make up for a sudden increase in demand above current supplies. What happened after 2003 was that these contracts became a major source of speculation, rising by some 850 million paper barrels by 2007. In practice, it is not clear precisely how many paper barrels there actual were by 2008. OPEC put it at an astonishing 496 billion, which is probably an exaggeration. The point here is that the paper barrels did not actually require ownership of any oil, as this would not in practice be remotely possible. On the contrary, all that was required was to place a bet on the price of oil at a particular price on a particular date, take your winnings or pay up according to the published price.

Opinions differ as to whether this made much difference to actual price. Either way, having some $60 billion invested in paper barrels at the start of 2008 must have had some effect, not least because when the US started to increase fracking and it became obvious that US oil shortages were rapidly diminishing, speculation in paper barrels rapidly halved. Either way, as a form of betting, it lacks both the employment opportunities and the excitement of horse racing. It is difficult to think of anything that involves as much money and is less valuable to human prosperity.

The next great apparent crisis occurred in 2022, largely as a result of Putin’s invasion of the Ukraine. Here the main impact was to shift Russian oil exports in the direction of China and India, rather than Europe. The price of Brent motored up in June to $122 a barrel, then quickly and conveniently motored down again to $79. More important for Europe was the price of natural gas, which greatly increased levels of inflation and it is a great mystery as to why their prices are so closely intertwined. They should not be, not least because they have very different uses. As far as oil is concerned, if the series of regular spikes in price show anything from their history, it is that the industry reacts much more rapidly to signals of shortage now than it did in the 1970s.

This does not mean that it has less economic impact than it did, but rather that the geo-political oil price panic is often more short-term than it used to be. This, in many ways, will make oil and its combustion effects more difficult, rather than easier, to reduce than the optimistic climate change activist would like. For a start, its roles in the economy are very extensive or more specifically, its distillation into its fractions defines those roles. You cannot for example, get rid of all gasoline in cars by electrification and still have as much jet-kerosene for planes. Equally, if you want lighter hydrocarbons for plastics like ethylene, you still end up with a lot of heavy fuel oil you do not want to put into ships. Oil is “all or nothing”; the heavy stuff comes up with the lighter fractions.

Equally the quality of crude differs across the globe, conveniently measured by the American Petroleum Index, or API. This derives from the specific gravity of crudes and varies enormously from the 73 API of Terengganu crude from off Malaysia to 19.8 API from the Canadian tar sands. The higher the API the better is the crude for the purposes of making fuels like gasoline. It is also the case that some crudes contain a lot of sulphur, which varies from nothing to nearly 4%. Ideally, to please an oil man, the best available crude ranges from 35-45 API, with as little sulphur as possible.

While these differences can be alleviated by refining, refining is an energy intensive business in itself. So ideally, if we are going to stop using crude oil, we should stop producing the heavier, high sulphur crudes first. This however produces a dilemma that is present in the whole idea. If we are going to ban the production and consumption of crude oil, whose economy is going to bear the loss of income from it? Saudi Arabia, the USA, Russia, or some of the smaller ones like Nigeria, the UAE, Kuwait, Brazil, Iraq? This is no longer about companies, but about countries, which may well lose significant proportions of their GDP.

After all, at say $79 a barrel, with a production of 90 million barrels a day, we are talking about removing $7.1 billion a day, or just under $2.6 trillion a year from the world’s oil producers. This is not, needless to say, something that will happen because someone – short of the Almighty – says it will. Or indeed, because billions of people say it should. It can only happen because those billions of people stop buying it. And that means finding a way of substituting its combustion with other ways of providing what it does for us.

Even then, given the capacity of the oil industry to continue to supply it, a reduction of oil’s use in some countries will likely have the effect of reducing its price. This price reduction will increase its use in other places, where the resources are not available to replace it. The process of reducing the use of oil was never going to be easy.

And yet, at long last, there is a huge amount of research going into mechanisms for oil substitution in steel-making, cement and glass making. Electric vehicles are on the rise as are experiments in hydrogen aircraft. Fuel cells too are coming on. Meanwhile banks are increasingly aware of public unhappiness about funding the oil industry. Certainly, radical lifestyle choices are now being made in the developed world particularly amongst the young. Restrictions are now being put on where you can drive in urban environments. The concept of the “15 minute city”, where facilities are a walk or bike ride away is catching on.

In addition, while the arrival of “peak oil” which created such alarm in the 1980s has turned out to be an illusion, there seems little doubt that oil needs a constant increase in its per barrel price to sustain its growth as the primary supplier of global energy. “Easy” oil is certainly running out. Offshore oil in deeper water requires more money to extract, while fracking, which returned the US back to its role as the leading oil producer has diminishing returns. Oil may not be running out, but the industry cannot keep the supply increasing at the current rate, at least by very much, if the price starts to fall. At current levels of production, the global reserves to production ratio (R&P) suggest that we can carry on like this for another 60 years. However, perhaps in quiet tribute to their statistician Dusty Miller, BP recently announced that it did not see ‘reserve replacement’ as a meaningful measure of success.

* This is a gross libel. It can be a lot of fun, and lucrative if you have a decent futures contract…er…contact!